Band Runway

The Physics of Compensation Nobody Talks About

Every compensation model I inherited before building my own operated on the same unexamined assumption, that a person’s value to the organization increases monotonically with time. Hire someone at a competitive salary, adjust upward annually (3%, the industry default, a number that feels generous to employees and negligible to finance) and let the accumulation compound. Tenure == value. Loyalty == worth. Staying is its own justification.

I never questioned this. Not through investment banking, where compensation was a weapon. Not through my first startup, where I was too busy surviving to think about compensation architecture at all. Not even in my early Shutterstock years, when I was building the career framework that would eventually force the question.

The question arrived not as theory but as arithmetic. I was modeling band ceilings for 350+ engineers across multiple continents, and the math kept producing the same result. No matter how I structured the bands, the 3% annual adjustment—the raise everyone treated as a reward—was also a countdown. Every year it moved an engineer closer to a ceiling that the organization had already defined. And nobody was tracking the convergence. Not the engineers. Not the managers. Not finance.

The engineers didn’t know there was a ceiling until they hit it. The managers didn’t know their reports were approaching it until a compensation review surfaced a number that couldn’t go higher. Finance didn’t know the cost pressure was building until it arrived as a budget crisis. Everyone was operating inside a system with hard structural constraints, and nobody could see them.

I built a model to make those constraints visible. Not to punish tenure, not to pressure anyone out of a role, but to give every participant in the system (the engineer, the manager, the finance team) a shared, transparent understanding of the physics governing compensation at each level. The band ceiling is a budgetary boundary. It exists whether or not anyone models it. The question is whether the organization surfaces that boundary early enough for everyone to plan around it, or whether it discovers the boundary through a crisis that nobody anticipated because nobody was looking.

The Convergence Problem

The standard compensation lifecycle works like this. An engineer is hired at a competitive salary within the defined band for their level. Each year, they receive a cost-of-living or merit adjustment, typically between 2% and 5%, with 3% being the gravitational mean. These adjustments compound. Over five years, a 3% annual increase on a $170,000 base produces approximately $197,000. Over ten years, roughly $228,000.

The band, meanwhile, has a floor and a ceiling. It gets recalibrated against market data periodically (annually if the organization is disciplined, less frequently if it isn’t) but the ceiling for any given level represents the organization’s maximum valuation of that role. It is a structural assertion: this is what this work is worth to us, at most, regardless of who does it.

The math is straightforward and the outcome is deterministic. The salary compounds upward through annual adjustments. The band ceiling holds. At some point, these lines converge. The engineer’s salary reaches the ceiling of their level’s band, and the system faces a decision. Promote them into a new band with a higher ceiling, accept that their compensation has plateaued at this level, or, most commonly, ignore the situation entirely.

Most organizations choose the third option because they never see the convergence coming. The engineer sits at the ceiling. Maybe they get a token adjustment, maybe not. They don’t understand why their raises have evaporated. Their manager doesn’t have a framework for the conversation. Finance is frustrated by headcount costs they can’t explain. Everyone is reacting to a constraint that was always there, encoded in the band structure from day one, but that nobody modeled, nobody communicated, and nobody planned for.

This is not a performance problem. It is a visibility problem. The constraint is structural. The failure is that nobody mapped it.

When I talk about coherence (the structural alignment between what an organization claims to value and what its systems actually produce) this is a textbook case of incoherence. The organization says it values growth, development, and transparent compensation. The compensation architecture contains a hard ceiling that nobody can see, approaching at a rate nobody has calculated, with consequences nobody has planned for. The stated value and the operational reality diverge. The gap between them is the space where misaligned expectations accumulate, where surprise attrition originates, where managers and engineers and finance all end up reacting to a crisis that was always predictable.

The Decay Function

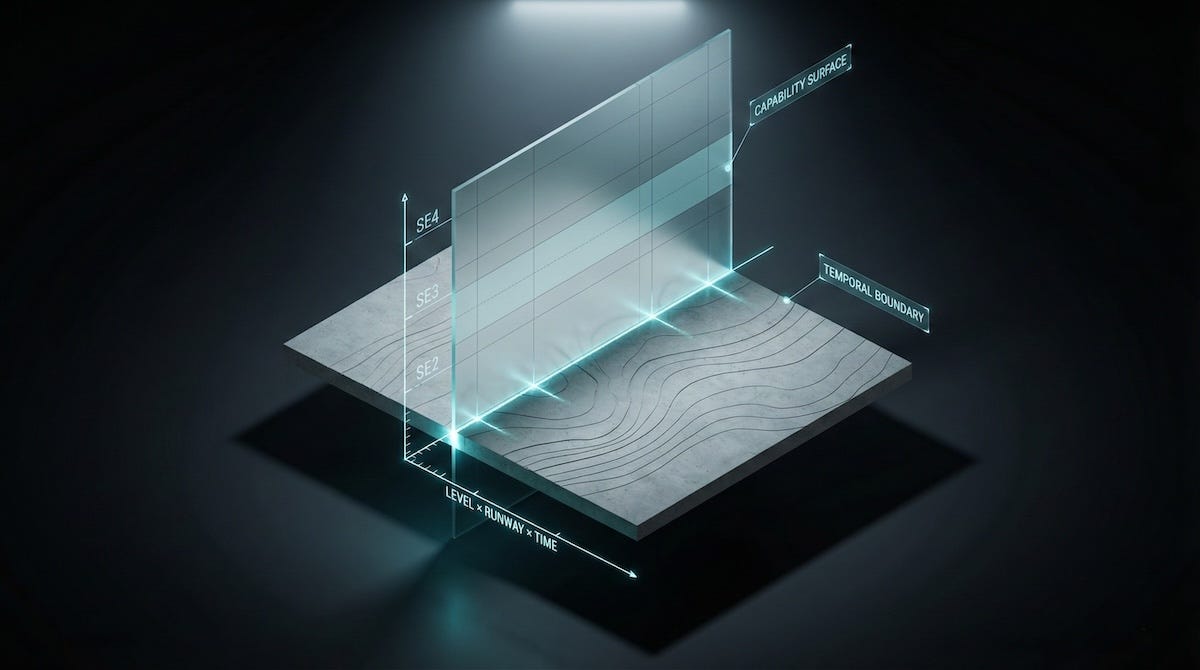

The model I built at Shutterstock, and later refined at Candid, introduces a temporal dimension to compensation planning that most organizations lack entirely.

In a traditional model, time is invisible. An engineer gets annual adjustments. Their salary grows. At some unspecified future point, they might hit the ceiling. Nobody knows when. Nobody plans for it. The system treats compensation as a monotonically increasing function with no boundary, as though the band extends forever, as though the raises can continue indefinitely, as though the convergence will never arrive.

The model makes the timeline explicit. Every annual adjustment, the same 3% that feels like recognition, simultaneously moves the engineer closer to the band ceiling. The distance between current compensation and the structural maximum shrinks with every adjustment cycle. I call this dynamic Band Compression, annual adjustments compress the individual against the band ceiling over time, converting what feels like open-ended growth into a bounded runway with a calculable endpoint.

At any given level, the band defines a floor and a ceiling. An engineer enters the band, either through hiring or promotion, at some point between floor and ceiling. Each annual adjustment moves them closer to the ceiling. The number of years before they reach that ceiling, the band runway, is determined entirely by their entry point and the ceiling’s position. This number is knowable from day one. It is not a mystery. It is basic arithmetic.

The headroom curves for both IC and management tracks illustrate this directly. Every level begins at 100% headroom and descends toward 0%, with the slope determined by band width and entry point. The VP (M8) reaches the boundary faster than the Engineering Manager (M4), an implicit structural assertion that executive-level compensation converges sooner because the bands are narrower relative to the adjustment rate, and the organizational cost of unplanned convergence at senior levels is correspondingly higher.

These curves are not predictions of performance. They are not judgments about capability or commitment. They are budgetary planning horizons. A map of when the compensation architecture will require a decision at each level, visible from the moment someone enters the band.

The annual adjustment is not just a reward. It is also a tick of a clock that the organization has already set. Every organization gives 3% raises. Almost none have modeled where those raises lead. Band Compression makes the destination visible so that everyone (the engineer, the manager, finance) can plan for it rather than be surprised by it.

A necessary caveat on scope. Band Compression models base salary against band ceilings. Base salary is not the totality of compensation, and the model does not pretend otherwise.

At senior IC levels and throughout the management track, equity becomes an increasingly significant component of total compensation, and equity operates on fundamentally different structural dynamics than base. Equity is granted in discrete events (initial hire, promotion, annual refresh), governed by vesting schedules, subject to valuation changes the organization may or may not control, and calibrated against a different set of market benchmarks than base salary. It does not compound at 3% annually. It does not compress against a fixed ceiling in the same deterministic way. It is, architecturally, a completely different compensation instrument.

This distinction is notable because at senior and executive levels, base salary plateaus are not failures of the system, they are expected features of it. A VP whose base has reached the band ceiling is not in crisis. The compensation architecture at that level assumes that equity, not base, is the primary growth mechanism. Band Compression’s diagnostic value at these levels is not “this person’s total compensation has stagnated” but rather “this person’s base has reached its structural maximum, which means equity strategy and promotion planning should be the active conversation.” The model identifies when one instrument has been exhausted. It does not claim that exhaustion means the orchestra has stopped playing.

What Becomes Visible

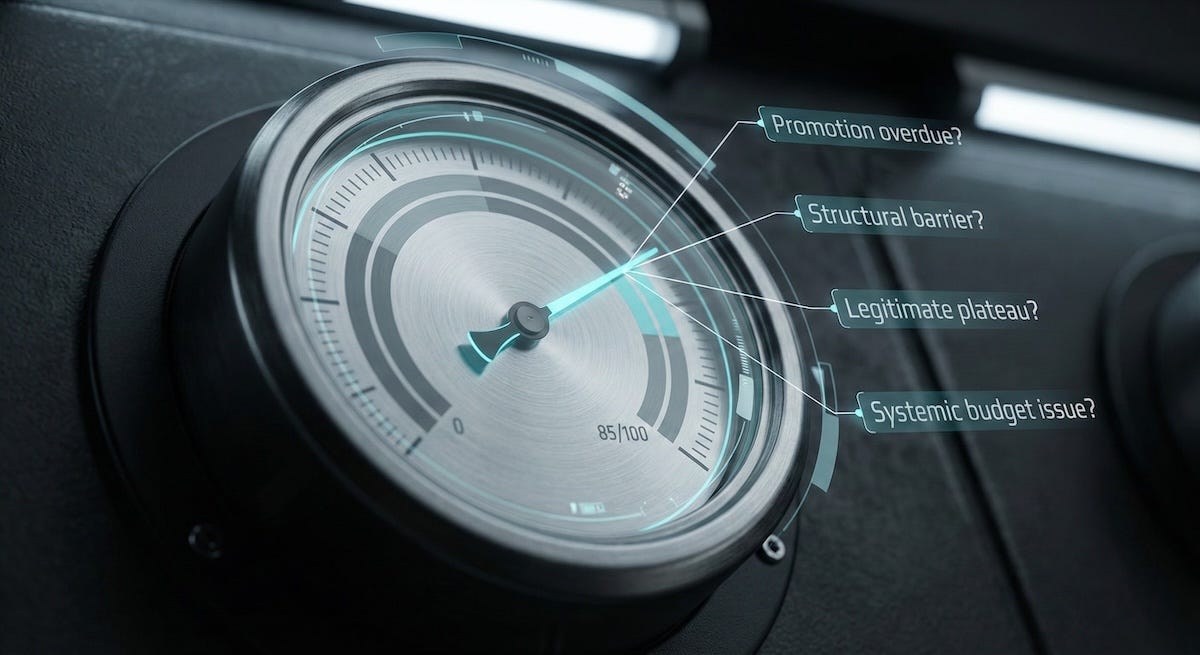

When an engineer’s salary approaches the band ceiling, the model produces a signal. That signal is not a verdict. It is a diagnostic prompt, a structured occasion for a conversation that might otherwise never happen, or happen too late, or happen in the wrong register entirely.

The questions the signal surfaces are genuinely exploratory, and this is where the model’s value as a management tool becomes concrete.

Perhaps the engineer is operating at the next level and the organization hasn’t formalized the promotion. This happens constantly. Engineers outgrow their level and nobody initiates the conversation because the system provides no structural trigger. The model surfaces the gap between actual contribution and formal level, giving the manager data to advocate for a promotion that may be overdue. The signal isn’t “this person is stagnating.” It’s “this person’s compensation trajectory is about to exceed what the organization has defined for this role. Is their actual contribution already exceeding it too?”

Perhaps there are structural barriers to advancement that the organization hasn’t addressed. The team doesn’t have the scope to demonstrate next-level impact. The promotion criteria are unclear. The manager hasn’t invested in development conversations. The model doesn’t answer these questions, but it ensures they get asked before the ceiling arrives and creates a crisis of misaligned expectations on both sides.

Perhaps the engineer has genuinely chosen to stay at this level, and that choice is legitimate. This is particularly true at what we defined in the career framework as breakpoint levels, Senior Engineer (SE3) and above, where the framework explicitly accommodates long-term tenure. If someone prefers depth over advancement, the model doesn’t penalize that choice. It makes the compensation implications of that choice transparent and mutual. The breakpoint says you can stay here. The runway curve says here is what “here” looks like financially over time. The framework is the map. Band Compression is the clock.

And perhaps (this is the signal most organizations never receive), the budget itself is incoherent. If a significant number of engineers across multiple teams are approaching their ceilings simultaneously, the model surfaces a systemic issue. Either the bands are too narrow, the leveling criteria are miscalibrated, the promotion pipeline is clogged, or the organization is growing more slowly than its compensation structure assumes. These are budgetary and structural risks that finance and leadership need to see before they manifest as attrition, compression grievances, or unplanned headcount costs. Band Compression gives them that visibility. Without it, the risks surface as crises. With it, they surface as planning data.

The model doesn’t answer any of these questions. It forces them to be asked. The traditional system suppresses them entirely.

The Architecture of Growth

Connect Band Compression to the leveling framework and something architectural emerges; the same kind of structural coherence I described in The Anatomy of Coherence, where stated values and operational incentives converge into a system that produces what it claims to produce.

The framework defines capability at each level; the specific behaviors, impact, and domains expected of an SE2 versus an SE3 versus an SE4. Band Compression defines the planning horizon, the timeframe within which the organization should expect to have a conversation about trajectory at each level, encoded not as managerial opinion but as compensation physics. The framework says what growth looks like. Band Compression says when the conversation about growth needs to happen. Together, they form a single architecture, one that makes both the destination and the timeline visible.

An engineer at SE2 has a defined runway. The band for SE2 has a ceiling. The 3% annual adjustment is counting. If they are approaching the ceiling, the model surfaces a planning trigger: the manager, the engineer, and potentially the skip-level should be discussing trajectory. Maybe the engineer is on track for promotion and it’s a matter of timing. Maybe they need targeted development. Maybe the criteria for SE3 aren’t clear enough and that’s a failure of the framework, not the individual. The model creates the structured occasion for these conversations before the ceiling arrives as a surprise.

The interaction between framework and model also addresses a subtler organizational challenge, the difference between consistency and trajectory. An engineer can be reliably excellent at their current level for years. Their work is solid. Their output is steady. Their peers respect them. In a system without Band Compression, this consistency is rewarded with raises, and the raises create an implicit impression of forward momentum even when the engineer’s level hasn’t changed. Neither the engineer nor the manager has a structural impetus to discuss whether the current trajectory is intentional or defaulted.

I encountered this pattern repeatedly at Shutterstock—engineers who were genuinely strong at their current level, doing excellent work, receiving positive reviews, and whose managers had no mechanism, no structured occasion, and frankly no data to initiate a conversation about trajectory. Not because the managers were avoiding it. Because the system never surfaced it. The annual review said “meets expectations.” The annual raise arrived. Everything felt like it was working. The convergence was invisible until it wasn’t.

Band Compression introduces the prompt by making the ceiling a known quantity with a known timeline. The engineer who is consistently strong at SE2 for several years is not being punished by the model. The model is surfacing a question: is this trajectory intentional? If it is, if the engineer has chosen depth at their current level and the organization supports that choice, the model’s value is in making that choice explicit and mutually understood. If it isn’t, if the engineer assumed they were progressing and nobody told them otherwise, the model’s value is in forcing the conversation before the ceiling arrives and the misalignment becomes a retention crisis.

This architecture governs the IC track and the management track identically. Band Compression applies to engineering managers, directors, and VPs with the same structural logic. The band defines the runway, the adjustment rate defines the timeline, and the ceiling surfaces the planning trigger. The physics don’t change with title.

The Constitution of the Band

The most common way managers inadvertently defeat this architecture is at the point of hire.

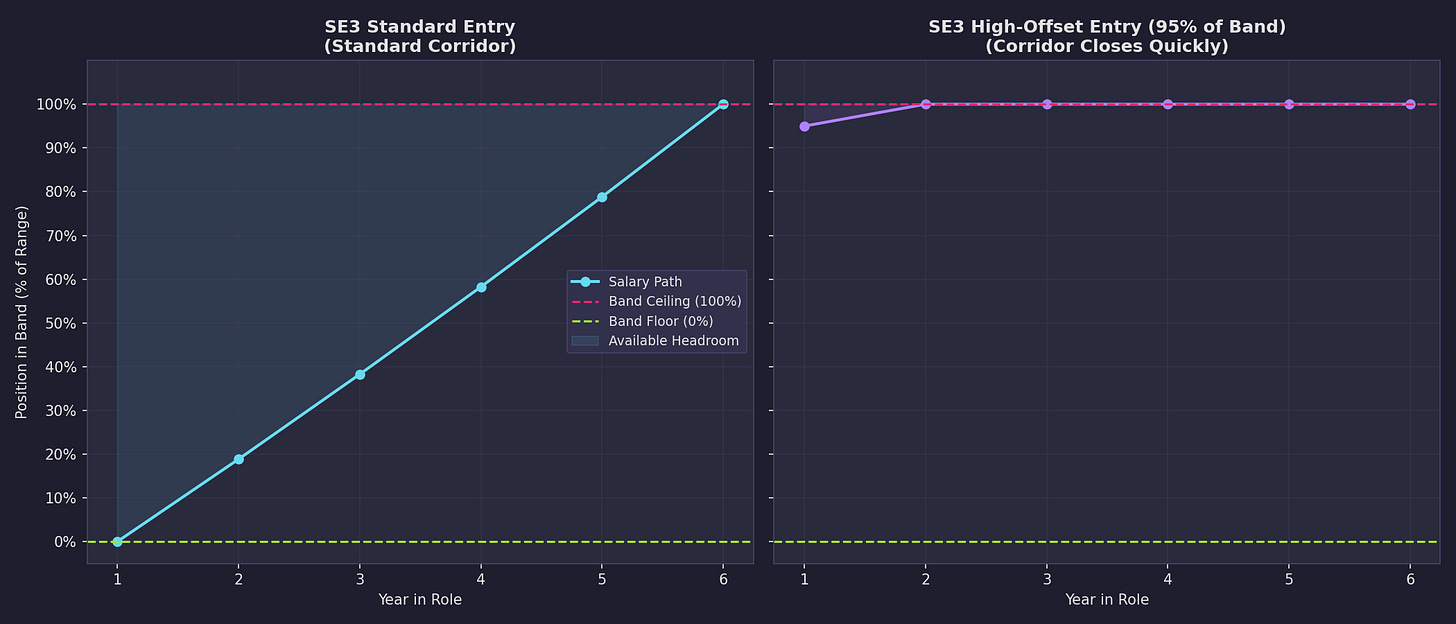

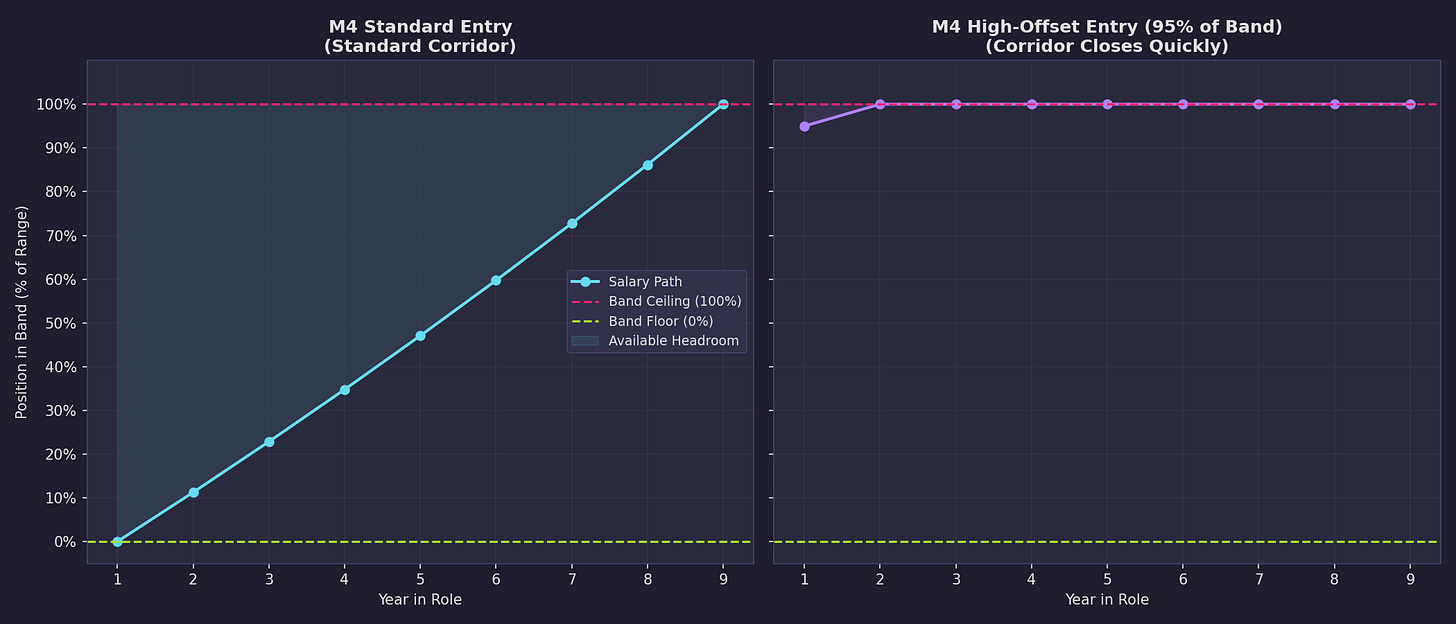

I wrote in Coherence about structural incoherence, the gap between what an organization’s systems claim to encode and what they actually produce. The hiring process is where Band Compression is most vulnerable to exactly this kind of incoherence, and the mechanism is disarmingly simple. Managers treat the band as a negotiation range when it is, in fact, a temporal architecture.

The compensation band defines a bounded space. Floor to ceiling, it represents the full economic range the organization has defined for a given level. Band Compression assumes an engineer enters somewhere in the lower-to-middle portion of that space, giving the annual adjustment vector room to travel before reaching the ceiling. That room is the runway. It is the temporal headroom within which the planning horizon operates. Compress the room and you compress the time. Eliminate the room and you’ve hired someone into an immediate ceiling condition on their first day, before they’ve written a single line of code, before they’ve had a single development conversation, before the model has had any opportunity to function as designed.

I watched this happen many times. A hiring manager eager to close a strong candidate escalates the offer. Then escalates again. The offer goes out at 90% or 95% of the band ceiling. The hire accepts. Everyone celebrates. The manager has their person. The candidate has their number. HR closes the req. Nobody has noticed that the planning horizon the model was designed to provide has been collapsed to near zero.

Within two adjustment cycles (eighteen months, maybe twenty-four) that engineer’s salary reaches the ceiling. The model surfaces the planning trigger. But the trigger is premature. The engineer hasn’t plateaued. They’ve been onboarding. The model’s signal is structurally correct but operationally meaningless because the temporal architecture was defeated at the point of entry.

The cascade from this single decision is instructive.

Internal equity distorts. The engineer hired at the top of the SE3 band is immediately earning more than an SE3 who has been growing into the band over three years of demonstrated impact. The tenured engineer is structurally less expensive despite having produced more value. The new hire’s salary reflects negotiation leverage, not organizational contribution. The system now contains an inversion that is invisible to the new hire, corrosive to the tenured engineer, and structurally indefensible to anyone who examines it.

The signal degrades. The planning trigger was designed to surface a meaningful timeline. When it fires for someone who was hired into the ceiling zone twelve months ago, it surfaces nothing except that the hiring process didn’t account for the model’s assumptions. The signal becomes noise. And noise, in any system, degrades the signal’s credibility everywhere else. If the ceiling trigger can be activated by a negotiation decision rather than an actual planning need, managers learn to dismiss it, and the model loses its value as a shared planning tool.

Retention economics invert. The engineer hired at the top of the band has minimal room for salary growth without promotion. Their annual adjustments (the 3% that everyone else experiences as recognition) become trivially small relative to their already-high base, or disappear entirely when they hit the ceiling. They went from a strong offer to a flat trajectory in under two years. They don’t feel like the organization is being transparent. They feel misled. Band Compression, which was designed to enable planning conversations, instead creates frustration that drives attrition.

The corridor charts make this visible. Standard entry preserves years of planning headroom. Entry at 95% of the ceiling collapses the corridor within two adjustment cycles.

The structural fix requires discipline at two points. Hiring guidelines must define not just the band but the target entry zone, the portion of the band within which offers should be made for new hires at a given level, preserving headroom for the model to function. Offers above the target zone require escalation and justification, not from the candidate’s perspective (candidate’s always want more), but from the model’s. What runway does this entry point provide? Is it sufficient for meaningful planning?

And managers must understand the topology. The band is not a discretionary playground. It is a clock. Hiring at the ceiling doesn’t make you generous, it removes the single tool the organization has for structured compensation planning at that level before the engineer has had any opportunity to demonstrate trajectory.

This is, once again, the distinction between mechanism and rhetoric. The rhetoric says “we offer competitive compensation.” The mechanism says “the entry point within the band determines the planning horizon for development conversations.” When managers optimize for the rhetoric at the expense of the mechanism, they defeat the architecture. They’re solving for the hire. The model is solving for the career. These are different problems operating on different timescales, and when the short-term problem wins, the long-term planning tool loses. Always. Across all scales.

Mechanism over Rhetoric

This is where the model exemplifies a principle I keep returning to; the distinction between mechanism and rhetoric that sits at the heart of organizational coherence.

Rhetoric: “We value a growth mindset.”

Mechanism: A compensation curve that decays relative to the band ceiling if you remain static.

Rhetoric: “We invest in career development.”

Mechanism: A leveling framework with domain-specific calibration tied to a temporal model that makes stagnation economically visible.

Rhetoric: “We reward performance, not tenure.”

Mechanism: Annual adjustments that function as a clock, not a reward, compressing against a structural ceiling that only promotion can raise.

Every organization I’ve encountered claims to value transparency. Almost none have built mechanisms that make compensation constraints visible to the people operating within them. The gap between the claim and the architecture is the space where misaligned expectations accumulate; the engineer who thought they were progressing, the manager who assumed everything was fine, the finance team blindsided by compression costs they could have forecasted.

Band Compression closes that gap. Not by changing what organizations say, but by changing what the compensation architecture reveals. When the framework says “we expect growth through levels” and the Band Compression model says “here is the timeline within which that growth matters financially,” the stated value and the operational visibility converge. That convergence is coherence. Its absence is where every misaligned expectation, every surprise attrition event, every compressed-salary grievance originates.

The Topology

I’ve described the physics of this model without sharing the specific numbers, and deliberately so. The dollar amounts are artifacts of a specific organization at a specific moment in time. They’ll be wrong within a year of publication and irrelevant within three. What matters is the topology.

The topology is this: a compensation band is an economically bounded space. An annual adjustment is a vector within that space. The ceiling is a structural boundary. The number of years before the vector reaches the boundary is a function of entry point and adjustment rate. That number of years defines the planning horizon at each level, the timeframe within which trajectory conversations should occur, budgetary risks should be assessed, and development investments should be made.

Any organization can build this. Define bands. Set ceilings. Model the adjustment trajectory. Calculate when each level reaches the ceiling. Publish the result, not as a threat, not as a performance management tool, but as structural transparency. Engineers deserve to know the physics of the system they’re operating within. Managers deserve tools that surface planning triggers before constraints arrive as surprises. Finance deserves visibility into compression risk before it manifests as unforecasted cost.

Bruce Webster documented the Dead Sea Effect,1 the dynamic where talented people leave and less mobile people accumulate, concentrating cost without corresponding capability growth. That dynamic is real, and it is a risk in any organization that lacks visibility into its own compensation physics. But it is a symptom of planning failure, not a character judgment on the people who stay. Organizations that surface constraints early, that arm managers with structural data, that provide engineers with transparent planning horizons, those organizations don’t produce Dead Sea conditions, because the conversations that prevent them happen before the accumulation begins.

I built the career framework at Shutterstock because I understood that ambiguity is the medium through which arbitrary power operates. I built Band Compression because I came to understand something adjacent, that invisibility is the medium through which structural constraints become crises. The framework made expectations visible. Band Compression makes the timeline visible. Together, they form an architecture where the stated values (growth, transparency, fairness) and the operational incentives converge closely enough that people can trust the system they’re operating within.

That’s the architecture. The same architecture, scaled and adapted, that I keep returning to across every system I’ve built or documented. Structure is not the enemy of freedom, it is the prerequisite for agency. And the first condition of agency is visibility. You cannot navigate what you cannot see or name.

Webster, Bruce F. “The Wetware Crisis: the Dead Sea Effect.” Bruce F. Webster, 29 Nov. 2008, brucefwebster.com/2008/04/11/the-wetware-crisis-the-dead-sea-effect/.